Mohammed Haider Hazaa Al-Dolae 1*, Adel M. Al-Najjar2, Mohammed Kassim Salah3, Ali Ahmed Al-Zaazaai4

1Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine& Health Sciences, Thamar University, Thamar, Yemen.

2Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine& Health Sciences, Thamar University, Thamar, Yemen.

3Al-Wahda Teaching Hospital, Ma'abar city, Thamar Governorate, Yemen.

4Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, PR, China

*Corresponding author: Mohammed Haider Hazaa Al- Dolae, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine& Health Sciences, Thamar University, Thamar, Yemen.

Received: October 05, 2023

Accepted: October 30, 2023

Published: November 22, 2023

Citation: Mohammed Haider Hazaa Al-Dolae, Adel M. Al- Najjar, Mohammed Kassim Salah, Ali Ahmed Al-Zaazaai. (2023) “Assessment of Diabetes Risk Among the Fifth and Sixth Years Medical Students in Thamar University, Yemen, A Cross-Sectional Study.’’. Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes, 3(1); DOI: 10.61148/CED/008.

Copyright: ©2023 Mohammed Haider Hazaa Al-Dolae. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly Cited.

Introduction: Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a global public health problem with a rising prevalence, leading to significant health and economic burdens. Lifestyle and environmental factors influence prediabetes and DM prevalence. Among the Middle East and North Africa regions, the prevalence of DM is particularly high. Early identification and management of DM are crucial to prevent complications. Lifestyle modification interventions have shown promising results in preventing T2DM. However, research on diabetes risk and lifestyle intervention among medical students is limited.

Objective: This study aimed to assess the 10-year risk of developing T2DM using the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) among fifth and sixth- year medical students in Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University, Yemen. Methods: This cross-sectional study involved 176 fifth and sixth-year medical students in Thamar University. A structured questionnaire based on the FINDRISC tool was used to collect data on risk factors, including age, BMI, waist circumference, physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, blood pressure medication, fasting blood sugar level, and family history of diabetes. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, and descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and student t-tests were used for analysis.

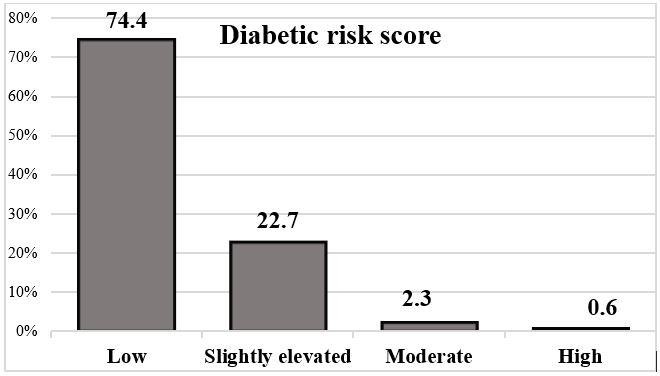

Results: Among the students, 22.7% had slightly elevated risk, 2.3% had moderate risk, and 0.6% had a high risk of developing diabetes based on FINDRISC scores. Overweight and obesity prevalence were 29%, and 14.77% had central obesity. Only 39.8% reported daily fruit or vegetable consumption. Regular physical activity was reported by 84.1%. Family history of diabetes was prevalent, with 55.7% reporting a first or second- degree relative with diabetes. Lower BMI, waist circumference, regular physical activity, no blood pressure medication, normal fasting blood sugar levels, and negative family history were associated with lower diabetes risk scores.

Conclusions: This study highlights the need for preventive measures and lifestyle interventions among medical students to reduce diabetes risk factors. Healthcare providers can play a vital role in promoting healthy behaviors and preventing type 2 diabetes among medical students, who serve as role models and future healthcare professionals. Implementing effective preventive strategies can contribute to reducing the burden of diabetes and improving population health outcomes.

Introduction:

Diabetes mellitus (DM), an alarming global public health problem, is a disorder of glucose metabolism that adversely affects the wellbeing of those who have it as well as their families, societies, and wider populations. According to estimates from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), there are currently 463 million people living with diabetes (prevalence: 9.3%) worldwide. This number is predicted to reach 700 million people (prevalence: 10.9%) by 2045 [1]. The economic burden of DM is highlighted by the significant global estimate of direct healthcare costs, which was 760 billion USD in 2019 and is anticipated to reach 845 billion USD by 2045 [2]. The health and financial burden brought on by DM is increased by prediabetes (intermediate hyperglycemia) and undiscovered type 2 DM (T2DM). Prediabetes, a transitional, highly risky stage for the eventual onset of T2DM exposes those who have it to microvascular and macrovascular complications [3- 6].

Prediabetes “marked as Impairment in glucose tolerance (IGT)” was estimated to have a global prevalence estimate of 7.5% in 2019 and is projected to rise to 8.6% in 2045. Additionally, many T2DM cases go untreated or unnoticed for years, during which time a serious complications may arise. An average of 50% (with a range of 24.1% to 75.1%) of people with diabetes are thought to be unaware of their illness worldwide [1, 7]. As a result, those with prediabetes and untreated T2DM pose a public health risk and present missed chances to prevent consequences [1, 7]

In addition to genetic predisposition, lifestyle and environmental factors also play a role in the observed variation in prediabetes and DM prevalence estimates between populations. In this regard, among US-based individuals, the prevalence of DM was reported to be 14.6% (diagnosed: 10.0%; undiagnosed: 4.6%), while prediabetes impacted 37.5% of the study group [8]. The prevalence of DM was reported to be 10.9% in Chinese study (diagnosed: 4.0%; undiagnosed: 6.9%), with 35.7% of the participants in the study had prediabetes [9]. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has the highest global age-standardized DM prevalence in 2019 among the seven IDF global regions, with a rate of 12.2% [1].

Along with acute problems, diabetes mellitus can also cause severe chronic sequelae as nephropathy, retinopathy, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc. Due to their chronic nature, many consequences appear after many years of the disease onset. Therefore, given diabetes control is the same, anyone with diabetes for a longer period of time is more likely to experience these consequences than those with DM for a shorter period of time [10, 11]. Moreover, a fast rise in the incidence of DM among young people has also been observed. This suggests that it is important to diagnose and manage DM at an early age in life [12-14].

Some research suggested that lifestyle modification intervention (LMI) has significant advantages in lowering glycated hemoglobin, fasting blood sugar levels, and body mass index (BMI) in the context to prevent diabetes [15].

Few trials have demonstrated the value of LMI and lifestyle counselling in preventing Type 2 diabetes [16]. Lack of health literacy has been linked to poor glycemic management, according to some literature [17].

Although the benefits of LMI in avoiding diabetes are well documented, studies on students is scarce. The success of diabetes prevention may depend on the early identification of risk factors and LMI. Therefore, the current study was carried out among 5th and 6th year medical students at a Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University in Dhamar governorate to assess 10 years risk for occurrence of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) using Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) and to investigate the association of risk of diabetes with other factors.

Materials And Methods:

Study Design: This study used a cross-sectional design to evaluate the risk of diabetes among fifth- and sixth-year medical students at Thamar University. The study was carried out during a two-month period (March to May 2023) at the Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University, Dhamar governorate, Yemen. Dhamar governorate (15°40’N 43°56’E) is situated in the middle of Yemen’s western highlands region, 1600–3200 metres above sea level.

Study Population and Sampling: The study population were fifth and sixth-year medical students enrolled in Faculty of Medicine, Thamar University during the study period. A convenience sampling approach was utilized, and students who were eligible were invited to participate. Students with known diabetes, those who were not available during data collection due to various reasons such as absence, sick leave, or maternity leave, as well as those who declined to participate, were excluded from the study.

Sample Size: The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula: N = Zα2 * P(1 − P) / d2. With a 5% margin of error (d = 5%) and a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), the initial sample size was calculated. Since the prevalence of prediabetes among medical students in Yemen was unknown, an assumption of 50% prevalence (P) was used. The formula was applied, resulting in N = (1.96)2 * 0.5 * 0.5 / (0.05)2 = 384. To account for the finite population size, the Adjusted Sample Size formula was then applied. The population size (S) was set to 265, representing the total number of fifth and sixth-year medical students during the study period. The adjusted sample size was calculated as N = (384) / {1 + [(384 – 1) / (265)]} = 158. Considering a 5% non-response rate, the minimum recommended sample size for the study was determined to be 166.

Study Tool: The risk of diabetes was assessed using the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) tool. The FINDRISC tool is a validated and widely used questionnaire that includes eight parameters; age, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, physical activity, daily consumption of fruit and vegetables, medications use for high blood pressure, level of fasting blood sugar, and family history of diabetes [18, 19]. Each parameter is assigned a specific score, and the total score ranges from 0 to 26. Based on the total score, participants are categorized into different risk levels: a score of less than 7 indicates low risk, 7 to 11 denotes slightly elevated risk, 12 to 14 signifies moderate risk, 15 to 20 indicates high risk, and a score exceeding 20 represents a very high risk of developing diabetes.

Data Collection: A structured questionnaire based on the FINDRISC tool was used to obtain the data. During regular class sessions or other convenient times, trained investigators distributed the questionnaire to the participants. For each participant, measurements of their height and weight were obtained. Participants were asked to stand barefoot while being measured in height to the nearest 0.5 cm using a wall-mounted measuring tape. A transportable electronic scale was used to calculate body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg, and the subjects were with minimum clothing and barefoot while measuring their weighs. BMI was computed by dividing weight (in kilogrammes) by height (in metres squared). The BMI results were then categorised in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) categorization system, with normal body weight falling between 18.5 and 24.9, overweight between 25.0 and 29.9, and obese falling between 30.0 and greater [14]. Using a flexible measuring tape, the waist was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at halfway between the lowest rib and the top edge of the iliac crest. The tape was wrapped horizontally around the waist to ensure it was snug without compressing the skin.

Data Analysis: The collected data were entered into a computer database, and the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 software. In order to describe the characteristics of the study participants and the prevalence of diabetes risk factors, descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviations, were generated. For categorical data, chi- square tests were performed, and for continuous variables, student t-tests. P 0.05 was set as the significant level.

Results:

A total of 202 medical students in their fifth and sixth years were invited to participate in the study, 26 of them were omitted as a result of the questionnaire’s missing data. Thus, 176 students were included in the final analysis, 77 of whom were female (43.7%) and 99 were male (56.3%). The age of the students ranged from 23 to 30 years, with a mean age of 25.96 ± 1.58 years.

In this young group, being overweight was frequent; overall, 29% of participants were either overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). To a lower extent a considerable number of the included students had central obesity; 26 (14.77%) had waists that were higher than the FINDRISC cutoffs of 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women. The majority of participants 148 (84.1%) reported engaging in regular physical exercise, which was outlined as at least 30 minutes each day of work or leisure.

Only 70 (39.8%) of the students reported daily eating fruits or vegetables. Fasting blood sugar equal or higher than 100 mg/dl was recorded in ten (5.7%) students. Unsurprisingly, only two students (1.1%) were on high blood pressure medication.

A first – or second-degree relatives with diabetes was reported by more than half of the included students 98 (55.7%). Overall, 47 (26.7%) students reported having a parent, sister, brother, or child with diabetes, while 64 (36.4%) students reported having a grandparent, uncle, aunt, or first cousin with the disease.

The FINDRISC risk score for developing type 2 diabetes in the following ten years among included students was ranged from 0 to 16, with a mean of 4.45 ± (3.41). A score of less than 7 was noticed in 131 (74.4%) of the enrolled students, putting them at low risk of acquiring diabetes. Among the students who got score more than 7, about 40 (22.7%) students scored between 7 and 11 indicating a slightly elevated risk, four (2.3%) students scored between 12 and 14 indicating a moderate risk, and one student (0.6%) got a score of 15 or higher indicating a high risk of diabetes [Figure 1].

The associations between characteristics and FINDRISC are shown in Table 2. There was no difference in the likelihood of developing diabetes across both sexes. The risk of developing diabetes was significantly lower among students with BMI < 25 Kg/m2 (P < 0.0001), students with waist circumference less than the FINDRISC threshold of 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women (P < 0.0001), students engaging in at least 30 minutes of daily physical activity (P < 0.0001), students not on high blood pressure medication (P < 0.032), students who had fasting blood sugar less than 100 mg/dl (P < 0.0001), and students with negative family history of diabetes.

|

Diabetes risk components |

No. of students |

Percentage |

|

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

|||

|

|

< 25 |

125 |

71% |

|

25 – 30 |

48 |

27.3% |

|

|

≥ 30 |

3 |

1.7% |

|

|

Waist circumference (cm) |

|||

|

Male (n = 99) |

|||

|

|

Less than 94cm |

87 |

87.9% |

|

94 – 102 cm |

12 |

12.1% |

|

|

More than 102 cm |

0 |

0.0% |

|

|

Female (n = 77) |

|||

|

|

Less than 80 cm |

63 |

81.8% |

|

80 – 88 cm |

12 |

15.6% |

|

|

More than 88 cm |

2 |

2.6% |

|

|

Daily 30 minutes of physical activity |

|||

|

|

Yes |

148 |

84.1% |

|

No |

28 |

15.9% |

|

|

Eating of vegetables or fruit |

|||

|

|

Everyday |

70 |

39.8% |

|

Not everyday |

106 |

60.2% |

|

|

Tacking medications for high blood pressure |

|||

|

|

Yes |

2 |

1.1% |

|

No |

174 |

98.9% |

|

|

Fasting blood sugar values |

|||

|

|

Less than 100 mg/dl |

166 |

94.3% |

|

100 – 125 mg/dl or higher |

10 |

5.7% |

|

|

Family history of diabetes |

|||

|

|

No |

78 |

44.3% |

|

Yes: Grandparent, aunt, uncle, or first cousin |

64 |

36.4% |

|

|

Yes: Parent, brother, sister, or own children |

47 |

26.7% |

|

Table 1: Diabetes risk components of study subjects (n = 176)

Figure 1: Risk of developing Type 2 diabetes

|

Characteristic |

Low |

Slightly elevated |

Moderate and high risk |

Total |

P- value |

|

|

Gender |

0.528 |

|||||

|

|

Male |

76 (58%) |

20 (50%) |

3 (60%) |

99 (56.3%) |

|

|

|

Female |

55 (42%) |

20 (50%) |

2 (40%) |

77 (43.7%) |

|

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

0.0001 |

|||||

|

|

< 25 |

107 (81.7%) |

18 (45%) |

0 (0.0%) |

125 (71%) |

|

|

|

25 – 30 |

23 (17.6%) |

21 (52.5%) |

4 (80%) |

48 (27.3%) |

|

|

|

> 30 |

1 (0.8%) |

1 (2.5%) |

1 (20%) |

3 (1.7%) |

|

|

Waist circumference (cm) |

0.0001 |

|||||

|

|

< 94 cm if male OR > 80 if female |

123 (93.9%) |

27 (67.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

150 (85.2%) |

|

|

|

94 - 102 cm if male OR 80 - 88 if female |

6 (4.6%) |

13 (32.5%) |

5 (100%) |

24 (13.6%) |

|

|

|

> 102 cm if male OR > 88 if female |

2 (1.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (1.1%) |

|

|

Daily 30 minutes of physical activity |

0.0001 |

|||||

|

|

Yes |

119 (90.8%) |

25 (62.5%) |

4 (80%) |

148 (84.1%) |

|

|

|

No |

12 (9.2%) |

15 (37.5%) |

1 (20%) |

28 (15.9%) |

|

|

Eating of vegetables or fruit |

0.570 |

|||||

|

|

Everyday |

54 (41.2%) |

14 (35%) |

2 (40%) |

70 (39.8%) |

|

|

|

Not everyday |

77 (58.8%) |

26 (65%) |

3 (60%) |

106 (60.2%) |

|

|

Tacking medications for high blood pressure |

0.032 |

|||||

|

|

Yes |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (1.1%) |

|

Table 2: Associations of characteristics among subjects with FINDRISK

Discussion:

Addressing the prevention of Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is an issue of utmost importance within the field of public health. Considering the evidence that lifestyle intervention can effectively prevent T2DM [20-22], there is a growing interest in developing tools to identify individuals at high risk. Such identification would enable targeted interventions or further testing of glucose metabolism using the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) [23]. The Finnish Diabetes Risk Score is a self-administered tool that can be utilized to identify individuals with a high risk of developing T2DM. It can also be applied in clinical settings and the general population to detect undiagnosed T2DM, poor glucose tolerance, and metabolic syndrome. Notably, our study stands out as the first study to investigate diabetes risk factors utilizing the FINDRISC among a medical students population in the Yemen.

The study included 176 students enrolled in the 5th and 6th year of medical graduate courses. Our findings revealed that 22.7% of the students had scores indicating a slightly elevated risk (between 7 and 11). A smaller proportion (2.3%) had scores suggesting a moderate risk (between 12 and 14), while only one student (0.6%) had a score of 15 or higher, indicating a high risk of diabetes. These results align with similar studies conducted in other countries. For instance, a study among medical students in Nepal by Sapkota et al. (2020) found a slightly elevated risk in 22.2% of the students, a moderate risk in 2.02%, and a high risk in 1.01% [24]. Similarly, a study in Jordan by S. Al-Shudifat et al. (2017) reported a slightly elevated risk in 26.2%, a moderate risk in 5.2%, and a high risk in 1.8% of their sample [25].

The majority of participants reported engaging in regular physical exercise, which is a positive finding indicating a proactive approach to maintaining good health among the students. However, the study also revealed a high prevalence of overweight and obesity among the participants, with 29% falling into these categories.

This finding is consistent with a previous study by S. Al-Shudifat et al. (2017), who found a prevalence of overweight and obesity of 23.2% among their study participants [25]. However, prevalence rates of overweight and obesity varied in other studies conducted in different countries. For example, a study by Singh et al. (2019) among medical students in India reported a higher prevalence rate of 45.7% [26], while a study by Sapkota et al. (2020) in Nepal found a lower prevalence rate of 11.5% [24]. It is important to note that cultural, dietary, and lifestyle differences can contribute to variations in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among different populations.

Regarding dietary habits, our study revealed that only 39.8% of the students reported daily consumption of fruits or vegetables. This finding is lower compared to studies conducted in other countries where higher proportions of students reported consuming fruits and vegetables regularly. For instance, a studies by S. Al-Shudifat et al., and (2017) Madalageri et al., (2021), conducted among university students reported a higher prevalence of 57.6% and 72.9% respectively [25, 27]. The lower prevalence of fruit and vegetable consumption in our study could be attributed to cultural and economic factors that influence dietary patterns in Yemen.

A noteworthy finding in our study was the high prevalence of a family history of diabetes among the participants, with more than half reporting a first or second-degree relative with diabetes. This finding is consistent with the results of a study by Madalageri et al., (2021), which also reported a high prevalence of family history of diabetes among medical students [27]. However, our study showed a much higher prevalence compared to the study by Ugwueze et al. (2022), which reported a prevalence of 14.2% [28]. The associations between various characteristics and FINDRISC scores were analyzed in our study, yielding significant results. Lower BMI, waist circumference below the FINDRISC threshold, regular physical activity, absence of high blood pressure medication, normal fasting blood sugar levels, and negative family history of diabetes were all significantly associated with lower risk scores, which were consistent with the results of previous studies. For instance, Melidonis et al. (2006) and Nyamdorj et al. (2010) reported a significant increasing the risk of T2DM as BMI increase [29, 30]. Khetan and Rajagopalan (2018) and Zheng et al. (2018) stated that a lack of physical activity was associated significantly with increasing the risk of diabetes [31, 32]. Ning et al. (2013) and Scott et al. (2013) reported a significant increase in diabetes risk among individuals with a positive family history [33, 34]. These similarities validate the findings and suggest that factors such as BMI, waist circumference, physical activity, and family history of diabetes play significant roles in determining the risk of developing diabetes.

In our study, there was no observed significant difference in the risk of developing diabetes between males and females. This finding is consistent with a previous similar study in Turkey by Sezer et al. (2021), which also found no significant difference between both sexes [35]. However, this finding contradicts other literature. For example, Evcimen et al. (2023) and Alazzam et al. (2020) reported a significantly higher diabetic risk among females [36, 37]. These discrepancies could be attributed to differences in sample sizes, genetic factors, or variations in the populations studied.

Conclusion:

According to the results of the study, it was observed that the risk of T2DM increased as the increasing of BMI level, increasing of waist circumference, high level of fasting blood sugar, lacking of physical activity, taking medication for elevated blood pressure, the presence of positive family history, and high level of fasting blood sugar. Although individuals' FINDRISC mean score is not high, an interventions measures are warranted to change preventable risk factors and promote healthy behaviors among medical students, who serve as role models and future healthcare professionals. By implementing effective preventive strategies, healthcare providers can contribute to reducing the burden of type 2 diabetes and improving the overall health outcomes of the population.